Living Lab Research Summary

This page provides a curated summary of academic literature and resources related to living labs, compiled by the living labs team at the University of Iowa. It highlights key research findings, definitions, and frameworks from a range of scholarly sources to help users better understand how living labs function as spaces for innovation, collaboration, and real-world problem solving.

The page is organized into expandable sections that explore different dimensions of living labs—such as their role in sustainability, education, and community engagement—making it easy to navigate and explore the academic foundation behind the living labs model. This collection is intended to support students, faculty, and partners who want to deepen their understanding of the theory and practice behind using campus spaces for experiential learning and research.

Literature Review: "A Systematic Review of the Literature on Living Labs in Higher Education Institutions: Potentials and Constraints"

Title: A Systematic Review of the Literature on Living Labs in Higher Education Institutions: Potentials and Constraints

Link to study: Here

Authors: Hacer Tercanli and Ben Jongbloed

This literature review explores how universities around the world implement and manage Living Labs (LLs) to advance sustainability, education, and community engagement. The authors analyzed 111 studies covering 93 university-led LL initiatives, finding that the best LLs integrate diverse stakeholders to create solutions to social and environmental challenges. Successful LLs also help higher education institutions (HEIs) embed sustainability into their teaching, research, and governance.

The review emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, stakeholder engagement, and applied research, aligning closely with the values of the University of Iowa’s Living Labs Working Group. LLs face both opportunities and barriers related to funding, institutional support, and faculty involvement. A key takeaway is that while LLs have strong potential for impact, their long-term success depends on strong institutional alignment, inclusive governance, and sustainable resources.

Sustainability Transition: "Conceptualization of Campus Living Labs for the Sustainability Transition: An Integrative Literature Review"

Title: Conceptualization of Campus Living Labs for the Sustainability Transition: An Integrative Literature Review

Link to study: Here

Authors: Claudia Stuckrath, Jesús Rosales-Carreón, and Ernst Worrell

This literature review helps define what Campus Living Labs (CLLs) are and explains how they work in higher education. CLLs use the campus as a real-world setting where students, faculty, staff, and campus operations work together to develop and test sustainability ideas. The authors use the term "campusian" to describe the people involved and highlight the importance of designing projects that meet their needs.

The review breaks CLLs into three main parts—place (the campus), network (the people involved), and approach (how the work is done). It also describes four ways CLLs can be run: Educational, Testbed, Strategic, and Grassroots. These different models show how CLLs can support hands-on learning, test solutions, drive campus goals, or grow from student and staff efforts. The review sees campuses as small-scale versions of society where ideas can be tested and improved before being used more widely.

Campuses as Catalysts: "Living labs and co-production: university campuses as platforms for sustainability science"

Title: Living labs and co-production: university campuses as platforms for sustainability science

Link to the study: Here

Authors: James Evans, Ross Jones, Andrew Karvonen, Lucy Millard, and Jana Wendler

This article explores how living labs can serve as a holistic framework for producing sustainability knowledge on university campuses. It is focused on the University of Manchester, where sustainability is a major academic focus. The authors identify three features that distinguish living labs from other high-impact practices:

They are embedded on campus.

They involve intentional, real-world experimentation.

They emphasize iterative learning—continuously refining ideas through feedback and experience.

The study also highlights the behind-the-scenes work that makes living labs successful, including physical setup, institutional coordination, and digital tools. Ongoing management is essential, with the authors stressing the importance of having dedicated teams to monitor, maintain, and adapt the space over time. Collaboration is vital as students, faculty, staff, and community partners must come together to address shared goals.

However, several barriers are noted, such as institutional hurdles (especially around funding), difficulties securing stakeholder engagement, and challenges in building visibility during early stages—when participation is most needed. Smaller labs tend to perform better, suggesting that scaling up requires careful planning.

Student Learning: "Mind the Gap! Developing the Campus as a Living Lab for Student Experiential Learning in Sustainability"

Title: Mind the Gap! Developing the Campus as a Living Lab for Student Experiential Learning in Sustainability

Link to study: Here

Authors: Tela Favaloro, Tamara Ball, and Ronnie D. Lipschutz

This article explores how the University of California, Santa Cruz is developing its campus as a living lab to enhance experiential learning in sustainability. The authors argue that addressing today’s complex environmental challenges requires interdisciplinary, real-world learning opportunities that go beyond traditional classroom settings. Living labs offer students the chance to engage directly with sustainability problems by experimenting, applying knowledge in practice, and reflecting through iterative learning.

The study identifies three core elements of a campus living lab system: the lab space itself, where teaching, research, and applied problem-solving come together; incubators, which are campus programs that offer structure and support for student-led projects; and coordinators, who act as connectors between students, faculty, staff, and programs. According to the authors, living labs are defined by being located on campus, involving intentional design or social interventions, and encouraging learning through repeated trial and improvement.

The study highlights a gap between the skills students develop in coursework and what is needed to participate effectively in living lab projects. There is often no clear pathway linking classroom learning with hands-on experiences, which can limit students’ ability to fully benefit from these opportunities. The authors propose a more integrated framework for experiential learning—one that combines mentoring, open-ended problem-solving, and meaningful social engagement.

Student Well-Being: "Planetary Health Begins on Campus: Enhancing Students’ Well-Being and Health Through Prairie Habitat Restoration"

Title: Planetary Health Begins on Campus: Enhancing Students’ Well-Being and Health Through Prairie Habitat Restoration

Link to study: Here

Authors: Bruno Borsari and Malcolm F. Vidrine

This study highlights how campus-based ecological restoration projects can promote student well-being and environmental awareness. At Winona State University, Professor Bruno Borsari led a prairie restoration initiative from 2006 to 2014, engaging over 800 undergraduate students in hands-on habitat restoration as part of biology and ecology courses. The goal was to evaluate how working directly with the land affected students’ health, well-being, and environmental outlook.

Through course surveys and focus groups, the study found that the prairie restoration experience was meaningful and beneficial for most students. Survey results showed a strong positive correlation between student participation and reported well-being. Students described a deeper connection to nature and greater personal fulfillment through their involvement in the restoration work.

The authors argue that this type of experiential, place-based learning supports a shift from human-centered (anthropocentric) thinking toward a more eco-centric worldview that recognizes Earth’s ecological limits. They recommend expanding this approach in higher education as a way to support both student health and broader sustainability goals.

Sustainable Development: "Universities as the engine of transformational sustainability toward delivering the sustainable development goals: 'Living labs' for sustainability"

Title: Universities as the engine of transformational sustainability toward delivering the sustainable development goals: “Living labs” for sustainability

Link to study: Here

Authors: Wendy Maria Purcell, Heather Henriksen, and John D. Spengler

This study explores how universities can use living labs to lead real-world sustainability efforts and help achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Living labs are outdoor or on-campus spaces where students, faculty, and community partners work together to solve environmental and social challenges through hands-on learning, research, and campus projects.

The authors share examples from three universities—in the UK, Bulgaria, and the U.S.—each using a different approach. One focused on changing its entire mission around sustainability, another built a leadership program for local business leaders, and the third used a campus sustainability office to support projects across departments. While the methods were different, all three used living labs to connect people, test new ideas, and make real change on and off campus.

The article shows that when universities align their teaching and research with sustainability goals and work closely with others, they can create long-term positive impacts for their students, campuses, and communities.

Find More Literature about Living Labs!

How to Teach Outside

Teaching outdoors opens the door to powerful, place-based learning that builds student curiosity, connection, and agency. Great outdoor learning doesn’t just happen because you’re outside, it requires thoughtful, intentional design.

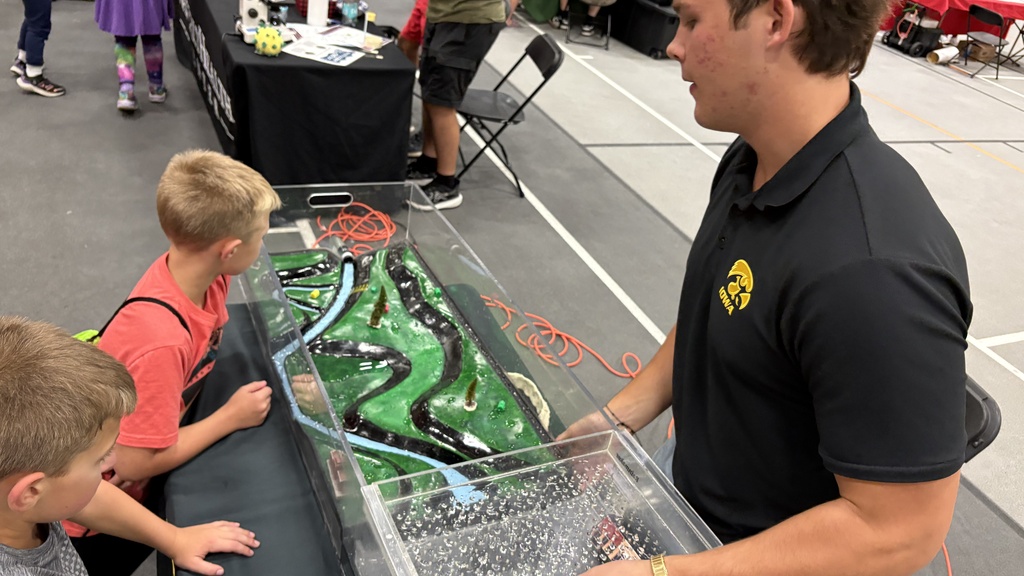

This section draws on insights from Ellen Carman (Program Coordinator at IIHR—Hydroscience and Engineering and the Iowa Flood Center) and Dr. Kay Ramey (Assistant Professor of Learning Sciences and Educational Psychology).

Many of the principles and ideas below are grounded in findings from Teaching in the Wild: Dilemmas Experienced by K–12 Teachers, a study led by Dr. Ramey and her collaborators at the University of Iowa. The study identifies key considerations for educators facilitating outdoor experiences, particularly through the lens of the School of the Wild program.

Read the full study at the button here: Link to article here.

(Ramey, K., Dunphy, M., Schamberger, B., Baradaran Shoraka, Z., Mabadeje, Y., & Tu, L.)

Design Principles for Outdoor Learning

1. Start with What You Notice

Let the natural environment guide the learning. Rather than beginning with a fixed lesson plan, invite students to observe, ask questions, and explore what's around them. A passing bird or unexpected turtle can spark just as much learning as a planned activity.

2. Let Students Lead the Inquiry

Offer prompts or phenomena instead of answers. Let students pose questions, gather evidence, and draw conclusions. This student-driven approach fosters deeper engagement, ownership, and critical thinking.

3. Embrace Movement

The outdoors naturally encourage physical movement—use it! Plan activities that allow students to roam, explore, and engage with the environment dynamically. Build in transitions between walking, observing, collecting, and reflecting to create a rhythm for learning.

4. Support Safe Exploration

Outdoor learning involves real-world risks, but these can be learning opportunities too. Set clear safety boundaries and expectations, then give students space to take appropriate risks, build confidence, and engage fully with the environment.

5. Think Beyond Subject Boundaries

Outdoor learning is inherently interdisciplinary. A single walk through the prairie might touch on biology, history, poetry, and art. Don’t let traditional subjects limit what’s possible.

6. Match Learning Goals to the Context

Some outdoor lessons can be tightly structured with clear objectives. Others may be more open-ended and responsive. Both are valuable, just be intentional. Adapt your structure to fit the goals, space, students, and moment.

7. Design for Relationships

Outdoor classrooms shift dynamics. Teachers often become co-learners, and the environment itself becomes the primary source of knowledge. Use this opportunity to strengthen student relationships, build trust, and foster a shared sense of discovery.

Living Labs can support both formal and informal teaching. What matters most isn’t how long you’re outside or how complex your activity is, it’s that the experience is designed with care, curiosity, and responsiveness to both the place and your students.

Did you know?

Time in green spaces is associated with lower levels of depression, anxiety, and negative emotions.